|

| American Graffiti co-writers, Gloria Katz & George Lucas. |

Many great filmmakers tend to revisit certain themes in their work and George Lucas is no exception. In his first three films Lucas has been very consistent in his themes and obsessions. THX-1138, American Graffiti, and Star Wars all share a certain continuity in ideas that are explored. With these posts I've attempted to extract and examine the themes and literary devices used in Lucas' second and best feature film.

YOU CAN’T STAY 17 FOREVER

Although change can be a scary concept, one can't hold on to history. Things change and life goes on. This point is illustrated in various ways throughout the film. For example, when Curt strolls down the empty school halls and tries the combination on his old locker he can't get into it; time has passed, and he can no longer be part of his old high school days.

|

| Young filmmaker, George Lucas |

The concept of moving forward and not living in the past is a major theme in Graffiti. Nobody knows this better than Lucas, himself. In 1987 George Lucas told Rolling Stone magazine, "I got to do what I wanted to do by not being frightened away by the future and the unknown, and I figured that was a good message to get across." Lucas stresses that life is a constant transition, and one has to accept that fact. Clinging to the past only leads to spiritual stagnation and other problems. In a 1974 interview Lucas illustrated this point, "You know, the brittle bow breaks. The willow bends with the wind and stays on the tree. You try to fight it, like John did, and you lose. You're not going to remain 18 forever."

A SIMPLE MOVIE WITH NOT SO SIMPLE METAPHORS

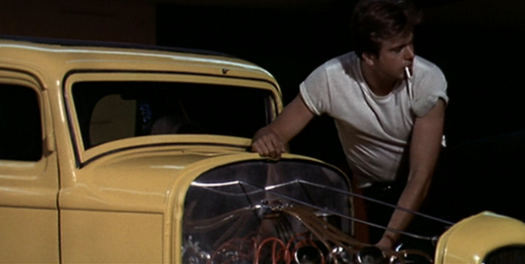

The use of cars in Graffiti works as a metaphor on several levels. The cars can be viewed as transporting the characters through change but also as limiting them. For instance, when the nerdish, Toad inherits his buddy’s elegant '58 Impala for the night he becomes much cooler. Just having a vehicle to drive up and down the circuit increases his chances with the opposite sex. On the other hand, John cruising in his little deuce coupe can be seen as a metaphor for stagnation. John is a 22-year-old teenager who notices that the cruising strip is "really shrinking." He has the sensation that things are changing around him and out of fear he desperately tries to cling to his adolescence; he is driving in circles and going nowhere.

|

| Is Milner just spinning his wheels? |

George Lucas has described cruising as a teenage mating ritual, where interaction takes place between the opposite sex. Through car windows young people communicate acknowledgements and flirtations. Some film scholars have identified cruising and particularly the car itself, in Graffiti as representing protection from a larger society. Writer Emanuel Levy is a good example of this viewpoint. In his book "Cinema of Outsiders," Levy notes that in Graffiti, the car window is a convenient shield to the outside world.

|

| Lobby card of '55 Chevy & '32 Coupe dragging the main. (click for larger pic) |

And, She'll Have Fun, Fun, Fun...

Lucas has said that he invented the blonde girl in the T-Bird as a metaphor for the ideal that is always just out of reach. In Graffiti, Curt chases the mysterious blonde all evening while she eludes

|

| The ideal is always just out of reach |

in a white dress and a white car. Some film scholars have pointed out the similarities between the blonde in the T-Bird and the green light at the end of a pier in The Great Gatsby. In the story Gatsby sees the green light as hope for a relationship with Daisy. Both the blonde in Graffiti and the green light in Gatsby are recognized as representing all of the protagonist's wants and desires which includes the elusive American Dream. Once Curt sees the blonde he is pulled into an emotion doomed to frustration and a desire impossible to satisfy. He becomes passionately committed to the unattainable. At the end of Graffiti, Curt realizes the futility of the pursuit. In the post script we learn after college he migrated to Canada to avoid being drafted into the Vietnam War. Once there he probably chose to chase another dream: writing THE GREAT AMERICAN NOVEL.

FASCINATION WITH CARS

There are close ties between Lucas' teenage car obsession and his filmmaking. This can be seen in his earliest work such as the1966 USC student film, 1:42:08: A Man and His Car. The wordless film depicts a race car driver, (Daytona designer, Pete Brock,) trying to qualify for a race in a Lotus at Riverside. He finishes the lap in 1 minute 42.08 seconds. Lucas was very pleased with his 5 minute, student film. "It was interesting to me because I was interested in cars and the visual impact of a person going against the clock," he recalls. Lucas made a more abstract experimental film (also from 1966), exploring the reflections of traffic on the glistening surface of a car at night. This theme of man and machine would reappear later. Lucas' first three features have some motor powered form of transportation that is crucial to the story..

RADIO IS FANTASY!

|

| The Emperor, Bob Hudson. |

In the past Lucas has said he found people's familiarity with technology particularly radio, to be intriguing. In 1973 he told Seventeen magazine, "Radio creates a fantasy that doesn’t exist at all except in your own mind." He first explored this theme in his 1967 USC student film, The Emperor. The B&W, 24 minute, film is an opus to Bob Hudson a very talented veteran southern California disc jockey. The film, in a jokey manner, comments on the background and popularity of the sarcastic DJ at KFWB and the idea that radio is a fantasy. The film is filled with a cool rock soundtrack of early sixties classics. Many people who've viewed this film find it to be Lucas' most enjoyable student effort. Although Hudson is featured in the 16-mm student project, the DJ was not Lucas' first choice for the part. In Dale Pollock's book, Skywalking, Lucas told the author, "I had always been interested in the phenomenon of radio and originally wanted to do the film with Wolfman Jack, but I didn't know where he was. I was amused by the fact that people have a relationship with a deejay that they've never seen but to whom they feel very close because they're with him everyday. For a lot of kids, he's the only friend they've got."

Fortunately, by 1972 the DJ had begun broadcasting a live 7-Midnight nightly show on the Los Angeles radio station, KDAY. Bob Smith aka Wolfman Jack was no longer the mysterious, elusive personality broadcasting from Mexico that he had once worked hard to foster. Locating him was easy. The co-writers of Graffiti, who lived several blocks from the station, approached him and he immediately agreed to be in Lucas' new film. With Wolfman acting as a Greek Chorus, seemingly commenting on all the action. Lucas was able to make the kind of movie that he really wanted to make. With his gravely voice, Wolfman Jack blasts rock 'n' roll tunes, makes prank phone calls (some staged, others real), takes requests, and creates a whole pre-recorded fantasy world that is aired from some undisclosed location. Although every kid in the film has their own idea or fantasy of what they imagine the Wolfman to look like, each feels that they know him personally.

He is their friend, father figure, and guardian angel all rolled into one.

He is their friend, father figure, and guardian angel all rolled into one.

Just like the omnipotent, OMM in THX-1138 and Obi-Wan Kenobi in Star Wars; Wolfman Jack in Graffiti is a God-like figure to the kids who listen to him every night.

______________________________________

NOTES

- Artifacts from the Future: The Making of THX: 1138. Prod. Dir. and Ed., Gary Leva. Supplementary to THX: 1138 Director’s Cut. DVD. (1970, 1998). Warner Brothers.

- Baxter, John. (1999). Mythmaker: The Life and Work of George Lucas. New York. Avon Books.

- Greenspan, Roger. (Aug 13, 1973). American Graffiti. New York Times.

- Levy, Emanual. (1999). Cinema of Outsiders. New York. New York University Press.

- Pollock, Dale. (1983,1999). Skywalking: The Life and Films of George Lucas. Updated Edition. New York, DeCapo Press.